Table of Contents

Interoception and a new view of emotions

Have you heard the term ‘interoception’ or ‘interoceptive awareness’ and wondered what is ‘interoception’?

Interoception is the sense of our own bodily sensations, and the topic is currently gaining attention among emotion scientists because of what this sense can tell us about emotions, and how it can be used to help manage emotions. In 2017 the book “How Emotions Are Made” was published by Professor Lisa Feldman Barrett. In that book, a quiet revolution hid behind its elegant and colourful cover. Barrett’s decades of research led her to the conclusion that our classical view of emotions could not be accurate.

The old view of emotions

The classical theories told us that emotions were universal and that all cultures had the same core emotions which were all expressed the same way and could be easily recognised in people’s faces. Over time studies showed that different cultures had different ways of expressing emotions and that even within one person an emotion isn’t always expressed the same. If you think of the difference between shouting aggressively and silently seething inside. These are both expressions of the emotion we call ‘anger’ but you might choose one over the other depending on the situation. It isn’t always clear what emotion is expressed just by looking at someone’s face. Take a look at these images:

What do emotions look like on our faces?

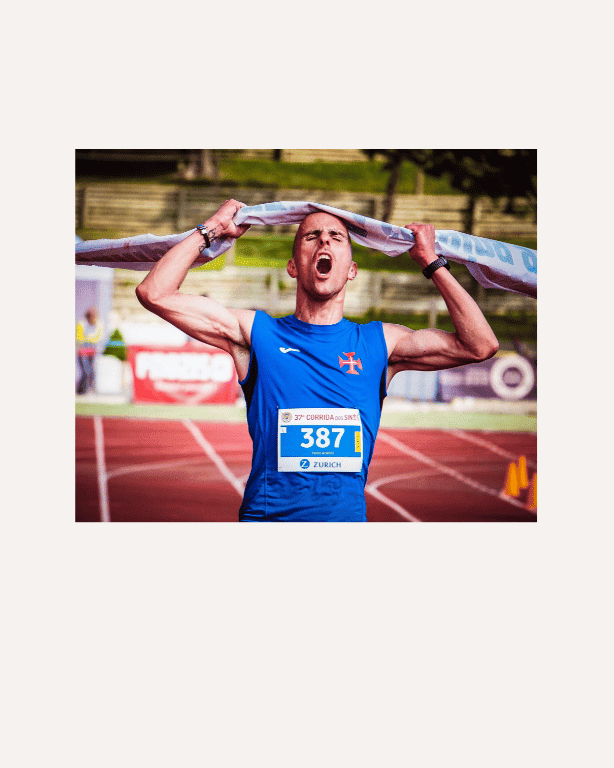

Is this pain, anger or something else?

Is this pain?

What do emotions look like in our bodies?

Now, look at these pictures with the extra contextual information that includes what the athletes’ bodies are doing:

With the extra information about this athlete’s clothes, where he is and what his arms are doing, it looks more like an expression of victory than pain.

In this image, as we zoom out and see where this athlete is and what her body is doing, we can see she is focused on successfully overcoming the hurdle. Instead of pain or anger, it looks like a combined expression of intense physical effort, concentration, and anticipation.

Did your judgment of what emotion was being displayed change when you had extra information? Look at pictures of Serena Williams playing tennis. Her face is so expressive and in moments of victory, if you zoom in on her face the expression can look like anger, but when you zoom out and see what her body is doing and where she is, you can see the expression is of victory. We think that it is just the face that can tell us what is happening inside for that person, but we are picking up information from the whole body and the context as well.

This shows that what our bodies are doing is also representative of what we are feeling. This is important to notice for ourselves and our emotions too.

How are emotions made?

Barrett’s studies of emotions also suggested that they are not always displayed in the same way each time we express them. The reason for this is said to be due to emotions actually being constructed in the moment each time they arise.

This construction of an ‘instance of emotion’ occurs due to our brain receiving and transmitting information from our body, via our interoceptive network and interpreting this information based on the concepts we have already learned. These concepts could also be called ‘schemas’, they are made up of what we have learned. So, a concept for feeling embarrassed could include the feeling of heat in our cheeks, how we think this will be seen by others, and what we should do when we feel this.

For example, if we are in a situation where we are feeling a hot sensation in our cheeks whilst speaking to others, this might trigger off the ‘schema’ in our brain of embarrassment and we might have thoughts about looking silly or saying the wrong thing, this would set off the anxiety about not wanting to appear that way and then the thoughts would increase, as would the fight/flight reaction and we will want to get out of the situation or do something to stop feeling anxious.

Which comes first, a feeling, a thought or a behaviour?

Our body and brain are in continual communication as the brain organises what fuel and activation are needed by the body to carry out the next task at hand. This is not a reactive process though. For example, if we see a snake and feel afraid, we might think that because we see a snake, we feel afraid and want to run away. This feels right to us because it seems to match with what we experience. But Barrett’s studies show that what actually happens is that our body and brain are already predicting what might happen in the current environment, based on past experience and this is taking place before we see the snake. We aren’t reacting so much as continually correcting and constructing simulations of what our brain thinks might happen. If we were purely reactive this would be inefficient and too slow for us to escape danger.

What is interoception and how does it work?

So what is interoception, and interoceptive awareness? The interoceptive network is like an information highway that transmits and receives information to and from our brain and body. This can be external information, such as heat, noise, how close someone is to us, and internal information, like our stomach rumbling, our gut aching or our hearts beating fast if we are running or exerting ourselves. A lot of what is transmitted will not be something we are conscious of, but this is going on even though we are not aware of it. Information about the safety or threat in an environment is also swiftly passed through this network from the autonomic nervous system as well.

Our brain coordinates and makes predictions about what resources are needed from moment to moment based on this information. For example, do the muscles need extra fuel so that we can run? Do we need to breathe faster, pump more blood around the system etc? All of this is happening outside of our awareness. It can make us think and act in certain ways as a result of what our brain predicts it thinks is happening.

Are our predictions always correct?

Barrett reported on a study of how it was shown that Judges made fewer parole decisions prior to lunch rather than after lunch. Some of the judges reported that they had a ‘gut feeling’ about the case and felt they did not want to grant parole to that person. However, these ‘gut feelings’ tended to be reported more by judges before lunch than after lunch. This raises the possibility that the judges’ brains were using the sensations of hunger as part of their decision-making when considering granting parole.

For people who suffer from panic attacks, the sensations they notice in their bodies can often be interpreted as dangerous. For example, the feeling of the heart beating faster can lead to the thought “My heart is beating too fast, I might have a heart attack!” This can mean that further fear is activated in their bodies because their brain believes something dangerous is happening that they have to get away from.

The brain then coordinates the sending of extra resources to the body to deal with the perceived threat. Except there is no threat so the extra fuel, oxygen, and muscle power are not needed. The person will likely experience a very strange set of sensations while their system has all of this going on inside until things eventually calm down and the body finds its balance point again. But if you are prone to panic attacks you will likely know that it can take many hours before all of this activity calms down, and it can be re-ignited very easily in that time too. A panic attack is very definitely not ‘all on your head’ as people used to cruelly say many years ago before it was known what actually happens in our bodies when we experience this. It is very physical indeed.

How can we use this knowledge to help with managing an emotion?

The way that we interpret our bodily sensations has a key role to play in the emotion that we construct. As A.D. Craig states:

“Sensations from the body underlie most if not all of our emotional feelings, particularly those that are most intense, and most basic to survival (Craig, 2015)”

We can develop our interoceptive awareness and this can help us to understand and regulate emotions more effectively. This means noticing the sensations in our body, and noticing the thoughts that we have about these sensations. Because the way that we interpret these sensations can be important if we are misinterpreting them. For example, a faster heartbeat does not have to mean that you are about to have a heart attack. The immediate rush to think that it does means that you then have to deal with the fight/flight program as well as your heartbeat and then things can become so much more unpleasant. It takes time but if we can just notice with curiosity first, then we will have the space to see what is really going on. In essence, this is about noticing how our body ‘speaks’ to our brain. What is your body saying right now?

Do a quick scan of your body and see if you can pick out any small sensations. Maybe a little pulse in your head, or a tight feeling in your calves. Are your neck or shoulder muscles feeling tense? The next time you feel irritated or surprised, notice the sensations in your body that are taking place. They have likely been there before you noticed you were irritated, but you may not have been aware of them. What we can aim to do is not just notice our bodily sensations when we feel a certain way, but learn to accept that they are there as a normal part of our emotional experience, and let them be.

Another thing you can do is sit with and notice the bodily sensations of an emotion the next time you feel upset, and watch how the sensations shift and change. Breathe slowly in and out, if you can. If there is no situation that you have to deal with right now, then tell yourself and your system that you can ‘stand down’. This way of managing an emotion can often be easier than trying to challenge the racing thoughts that go through our minds when we are upset.

Here’s an example; if you are about to leave work and your boss calls you back to ask you to do one more thing before you leave. The impulse is to have a rush of thoughts about this request, but if you were to also notice any sensations in your body, you might notice the rise of your heart rate, as well as the racing thoughts about what the boss asked you to do.

There might be things you want to say but because it is your boss you will have to restrain yourself in order to maintain the relationship with your boss. So you might agree to what the boss asks, but then be having thoughts about how you really feel about this and your body will be in an activated state by this time, with many sensations taking place. You might only notice the thoughts about the situation though, for example, “Why do they always do this when it’s last minute?” “Why can’t I just say no?!” You may not notice all the sensations in your body, or may not know what to do about them. When you leave work though, you might find that you express yourself to the next available ‘safe’ target, like another driver on the road, or your partner when you get home.

If though, you were able to notice the activation in your body and then breathe slowly to ‘talk yourself down’, with slow breathing and perhaps some discharging movements like shaking out your fingers or legs to get your body back to balance again. You can bring that activation down yourself. The experience is then less likely to lead to either rumination and further anger, or shouting and expressing anger at a safe target that may then lead to you feeling guilty or remorseful. Compassionate thoughts are key here too though, if you beat yourself up over why you said ‘yes’ to your boss, that will keep you activated. Likewise, the thoughts that you have about your boss are also likely to re-activate you. The thinking patterns sheet that we use in CBT can help a little with noticing certain patterns in our thinking and how these can quickly activate us, but yet they are not always true reflections of the situation, so we don’t have to believe them.

References

Barrett, L.F. (2017). How emotions are made. The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin.

Craig, A. D. (2015). How Do You Feel? An Interoceptive Moment with Your Neurobiological Self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400852727

Price, C and Hooven, C. (2018). Interoceptive Awareness Skills for Emotion Regulation: Theory and Approach of Mindful Awareness in Body-Oriented Therapy (MABT). Frontiers in Psychology. Vol:9. Pp 798. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00798